Complementarity

Operating System

The “both/and” principle for systems transformation — an operating system for the future.

Introduction

Complementarity is the unifying principle of Superior Branding Company — the engine of our creative practice, the approach to our relationships, and the mindset which we try to consistently orient ourselves to as a team.

After two years of reliance in this principle, we are sharing an introduction to complementarity. We hope that this information will help others develop more awareness about themselves, and realize more potential in the systems in which they work.

An Operating System for the Future

For now and into the future, the ability to work with others who have perspectives different from our own will be the most valuable skill we can cultivate.

Our current systems are failing because of their inability to hold multiple perspectives at once, or what we call binary, “either/or” thinking. Differences in our current model lead to tension, disfunction, and outcomes that benefit a few at the expense of many. Difference has been used to create social, racial, gender, and class hierarchies. Still, we continue to build our world from this one-sidedness, drawing from established binary models that consciously or unconsciously, seek to protect their own interest.

We see the effects of binary thinking nearly everywhere: in our political system, where it has produced an unbearable tension. We see it in the core of our technology platforms, reinforcing a competitive mindset in us daily. We also see it in the smaller systems of our own lives — in the dynamics with our colleagues, our intimate relationships, and in how we understand the differences within ourselves.

Difference is a given, but dysfunction is not. Differences are currently a source of tension and categorization — can they be a source of innovation, better outcomes, and benefits that are shared by all? How can we work with difference, not in spite of it?

Complementarity is the principle that holds difference not in tension, but in creative potential. As a mindset and practice for how we relate to others, complementarity is the ability to hold multiple viewpoints and possibilities simultaneously. In a world of seemingly endless strategic frameworks and new prescriptions for success, complementarity is a living principle, an expression of nature, not of ego. A term born from physics, our reality has complementarity built into it, down to the smallest levels of energy and matter.

In almost every system — social, political, digital, biological, the question is being asked: “Where do we go from here?” Complementarity, if we choose it, can be the principle from which we develop new systems and refresh existing ones. It is at once a reflection of creativity found in the world around us, an essential force for building stronger relationships, and, in its fullest expression, an operating system for the future.

Associations and Amplifications

Rather than writing a linear article, we’ve put together an associative presentation of complementarity — a unifying principle that can be amplified in many areas of our lives. Readers are encouraged to begin with whichever areas of amplification are of interest, and continue reading in this way. The areas below, and others to come, remain in continuous expansion.

Begin Reading:

In Physics

“All Reality is Interaction” – Carlo Rovelli

Complementarity is a principle so foundational to our reality that the term is borrowed from the study of quantum physics. This science is an investigation into how the smallest aspects of our world behave and interact.

We know from Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle that the act of observing something influences the measurement of the object observed. For example, you cannot precisely measure the position of something and its momentum at the same time, because the act of measuring position shifts the measurement of its motion. It is impossible to untangle the observer from the observed. Our perspective not only matters, it influences reality itself.

In the Newtonian model of physics, when we observe an object acting in a certain way, and assume that it is in its nature to act this way all of the time, we might consider this behavior is immutable and applicable across all other conditions. But when we begin to measure objects at a very small scale (quantum physics), another picture unfolds, and the reality we thought we knew behaves differently than we had previously observed. Even more, as we’ve learned from Heisenberg, as observers we participate in the output of an object’s measurement. Because of this dynamism, in the quantum view, we see objects not has having fixed properties, but having properties en potentia, based on an environmental field which we ultimately affect. With the model of quantum physics, we move from a fixed view of the world around us and its behavior, the reality of either/or, to a reality of many potentials. The last 100 years of physics has been an exploration in reevaluating the nature of our reality as a whole based on these new observations.

In both theoretical and experimental quantum physics, the principle of complementarity holds that objects have both “wave” and “particle” in their nature, and it is nearly impossible to measure them simultaneously. An object will express its “wave” aspect in one environmental field, and its “particle” aspect in another. This is known as the “duality paradox.” The physicist Neils Bohr regarded this paradox as a fundamental fact of our reality. When we are observing reality, there is always a complementary state that remains in unexpressed potential. With our traditional tools of measurement, we are only seeing one aspect of something at any given time.

Whether our lens be a scientific one, or simply a dominant mindset or worldview, it seems impossible to perceive the differing aspects of reality together simultaneously. We must make a paradoxical leap that reality is comprised of both wave and particle, and it is our own one-sided-ness in perceiving that convinces us it is always one or the other.

Quantum entanglement is another observed phenomenon that points to mysterious complementary relationships at the atomic level. Particles (electrons, photons etc.), behave with a spin in nearly all directions. When we measure the state of a particle, we observe one direction of spin as a snapshot - a particle that is spinning directionally up, for instance. When two particles are in a state of entanglement, whether through an interaction or a spatial relationship, they will show complementary directions of spin when measured. If one particle is spinning up, the other will be measured spinning down, and vice versa. Although they each have independent spin, by nature of their interaction they will always demonstrate a complementary relationship.

“To do full justice to reality, we must engage it from different perspectives. That is the philosophical principle of complementarity. Complementarity is both a feature of physical reality and a lesson in wisdom.” - Frank Wilczek, Nobel prize winning quantum physicist.

When we understand complementarity as a truth of our physical reality, we can use it as the metaphorical jumping-off point for how we perceive and relate to one another. Complementarity is literally the quantum leap for understanding the potential in a system, and then, by skillful means, unlocking the potential in that system.

The question for us as individuals trying to understand, and ultimately affect the systems in which we find ourselves in, is how to work with our own mindset and relational abilities to unlock the principle of complementarity? How can we hold difference — of perspectives, ideas, and even ideologies — not in opposing tension, but in the complementary reality that is their true nature?

Binary Thinking

Complementarity's Opposite

Although complementarity is a natural principle, our dominant perspective has been so shaped with binary, competitive, “either/or” thinking, that its power lays dormant. Unlike complementarity, which assumes that two or more aspects of reality can exist simultaneously, a binary lens can see only one aspect at any given time. This view is naturally disposed to categorization, hierarchy, and one-sided dominance. A binary lens measures something as a “particle” one time, and then fixes this view into a label, categorization, or identity. It doesn’t view what is emergent or in potential in the world around us.

The challenges that are found in our culture, if we are to reduce them, can be understood as over-identification with the binary mindset. This mindset allows only for one “right” answer or viewpoint at any given moment — the systems that result, even in their most complex, work only when one person or group holds the dominant view, and the other is under regarded, or worse, exploited. Binary thinking cannot hold multiple perspectives at once, yet we live in systems in which multiple perspectives are a given.

When two different perspectives in any system directly oppose each other the binary model holds them in tension, and only a dominant viewpoint can emerge. This happens through brute force or the “loudest voice,” or in its more subtle, systemic expression, the maintenance of power structures that continuously minimize one perspective and uphold another.

But what is the way through, then, that allows both perspectives not only to co-exist, but because of their polarity, be a pathway to new outcomes? Complementarity is not a middle ground between two opposing points of view. The complementarity relationship of black and white is not grey, it is closer to a yin-yang, where from the result of two opposing perspectives there comes a “third way” that includes both, and is only possible when these two perspectives meet each other in complementarity and not one-sided dominance. The result of complementarity is not an in-between, a compromise, or even that overused word “balance”, it is an innovation where the parts mutually reinforce the whole. Each individual perspective gains something as a result of this mindset, and intrinsically includes its “opposite” for more wholeness and integrity.

Carl Jung’s psychology understood the “opposites” not only as external ideas or forces, but internal parts of ourselves that can create difficult tension. Our job, according to Jung, is to develop new psychological disposition that integrates the opposites — “Psychologically, we can see this process at work…After violent oscillations at the beginning the opposites equalize one another, and gradually a new attitude develops, the final stability of which is the greater in proportion to the magnitude of the initial differences. The greater the tension between the pairs of opposites, the greater will be the energy that comes from them … and the less chance is there of subsequent disturbances which might arise from friction with material not previously constellated.” [“On Psychic Energy,” CW 8, par. 49.”]

Because we are disposed to ignoring the opposites within ourselves, they express themselves externally. We project the “opposite” onto another person or group of people, in a sense unconsciously using the external expression to work out the inner tension: “…When an inner situation is not made conscious, it happens outside, as fate. That is to say, when the individual…does not become conscious of his inner opposite, the world must perforce act out the conflict and be torn into opposing halves. [“Christ, A Symbol of the Self,” CW 9ii, par. 126.]

A complementarity view of opposites, internal or external, can lead to the integration of the opposites for an outcome that is more than either on their own — indeed integration is at the core of integrity. Systems of integrity and resilience do the work of integrating fragmented or opposing aspects into a unified, mutually-supportive whole.

With nearly all of our institutional and collective systems highly fragmented, we are in one sense starting from a very fertile place. The material is there, and therefore the invitation, to shift our perspective from a binary model to a complementary one. We do not yet see a “third way” because we have not yet made this shift as a culture, and the fragments of our whole systems remain in tension, not potential. The only solutions ahead are ones we cannot presuppose with an existing binary mindset.

Complementarity is not an outcome in itself, but a process of relating that leads to new outcomes. It is understanding our differing perspectives not as a hurdle to growth, but necessary for growth.

The Engine of Innovation

In systems of two people or small teams, complementarity could also be described as “collaboration across difference”. Some of our most incredible advances have come from complementary innovators, yet we remain largely unconscious to the conditions or architecture of these relationships. We refer to the “magic” or personalities that “just work” together. But what if we understood, and even more, consciously applied, the principles that forge these innovative relationships?

Culturally, we spend far too much time focused on successful outcomes and far too little time learning from the conditions and relationships that achieve successful outcomes. What are the mechanisms for collaboration? What has to happen in order for two or more people to collaborate successfully? Successful collaborative relationships reveal the hidden, mostly unconscious aspects of complementarity that we can learn from. We must investigate the mechanics of our relationships more than the outcomes we’re trying to achieve.

Successful collaboration involves not only having empathy for another’s perspective, but allowing that perspective to mutually reinforce our own, revealing the “other side” that exists in all collaborative relationships. This is something one-sidedness or narcissistic leadership can never achieve. In fact, one-sided innovation is a myth —remember Carlo Rovelli’s quote: “All reality is interaction.” Collaboration across difference allows for something new to happen that is more than an individual could have dreamed of on their own.

—

A powerful example of a complementary pair of innovators comes from science. Watson and Crick together discovered the nature of fundamental building blocks of life of biological life, DNA. What makes their discovery so interesting is that DNA itself is comprised of complementary pairs. The structure of DNA, the “double-helix,” extends the metaphor: Each DNA double helix is used as a template for creating a new “base-pair” or complementary strand, using what is referred to as a “lock and key” mechanism. “The Complementarity of DNA strands in a double helix make it possible to use one strand as a template to construct the other,” so, in biological terms, complementarity is at the heart of biological replication and creation.

Discovering the structure of the “double-helix” was something Watson and Crick each said they could not have done without the other.* Watson and Crick’s relationship was one of admiration, brotherly competition, and a shared focus on a very specific problem. In other words, they defined and agreed with a great specificity, the language and context of their work. We’ll see later, how “agreeing on terms” is one of the key practices of complementary relationships. *It should be noted that their discovery could not have happened without the contributions of Rosalind Franklin’s model of dual molecules.

Like Watson and Crick, Daniel Khanemen and Amos Tvaersky were complementary pairs whose innovations in behavioral psychology, like Watson and Crick’s double helix, expressed the principle of complementarity within their discovery. They developed twin modes of thinking: System 1 and System 2, to describe the linear, systematic processing and nonlinear, intuitive processing of the mind with regards to decision making. This model has a parallel to the relationship between conscious and unconscious aspects of our psyche, which is discussed elsewhere in this presentation.

Two of the founding members of the women's rights movement, Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, used their friendship and mutually supportive skills as a way to fight for women’s suffrage. Anthony was an outspoken, extroverted personality, serving as the vocal head of the cause. Stanton was her complementary partner, an introverted writer that could intuit and articulate the needs of the time. Together they united their complementary strengths around a common goal.

With complementary pairs, it is often the case that one partner is more seen or vocal than the other. If the more extroverted partner doesn’t navigate public attention with care and empathy, they can mistake attention for credit. Silent or introverted partners are key to complementary relationships, and their skillsets must celebrated rather than diminished or exploited. Relationships that are operating in complementarity are not over-identified in one aspect all the time.

With the development of Apple computers, we see complementarity in founders Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak. Wozniak was a technical, detailed and introverted. Jobs understood the humanity and far-reaching potential of personal computing, and also brought with him a visionary, almost mystical personality. Apple computers is a result of these twin aspects of personality and skillset into a new creation. This opened up a new consumer paradigm for an industry previously limited to technologically advanced few. Without each other, this leap would not have been impossible. Complementarity is still built into Apple, products that leap forward in both technological advance and ease of use; substance and style.

These “twin” relationships are more than 1+1=2. Each individual’s own dominant aspect is made stronger because of its complement. As Jung has it: “The meeting of two personalities is like the contact of two chemical substances: if there is any reaction, both are transformed.” It is nearly always the case that one individual is bringing to the system something the other does not have, or is underdeveloped in — sameness is not a recipe for creativity. Somehow, each individual must get out of their own way to allow the system to benefit from the two complementary ideas, practices, or skillsets, accelerating the potential for creativity. The practice becomes using difference, not avoiding it or getting stuck in one-sidedness. The concentrated example of a complementary pair can be amplified for larger systems, although as we can imagine it becomes much trickier.

There is no two-person system where complementarity can more directly applied than that of romantic relationships, and a discussion must has to be left for another time. Romantic relationships are the pressure-cookers which reveal the “other aspect” of our partner (and ultimately, our own, inner complements) and require us to empathically relate to difference. With a complementarity mindset, the commitments we make in romantic relationships can produce incredible bonds and creative partnership.

Evolutionary Biology

Since Darwin’s theory of evolution, competition as a biological imperative has been so worn deeply into our way of thinking that we take it as a given for how we relate and evolve in systems. There is something so brutally elegant about “survival of the fittest,” that we brazenly apply everywhere, but competition as the only evolutionary principle is not a sustainable model. How can a system — whether a hundred-person workplace or a 300 million person society — thrive, if its dominating mindset is “kill or be killed”? We have taken one observable model for evolution and applied it to wholly inappropriate contexts in which competition does noticeable harm to many, for the benefit of a select few.

Darwin’s theory of evolution, and resulting competitive worldview is not an idea born in a vacuum, but comes with it the program of the 19th century worldview. John Favini writes in his article on reaccessing Darwin’s theories for the time they were developed“…like all humans, Darwin brought culture with him wherever he traveled. His descriptions of the workings of nature bear resemblance to prevailing thinking on human society within elite, English circles at the time. This is not a mere coincidence, and tracing his influences is worthwhile. It was, after all, the heyday of classical liberalism, dominated by thinkers like Adam Smith, David Hume, and Thomas Malthus, who valorized an unregulated market.” Remember from quantum physics, we cannot observe without affecting our observation.

As our study of other species progresses, a wider picture comes into view. “Collaboration across difference” is being understood as an evolutionary driver alongside competition. Biologists are now studying inter-species symbiotic relationships, like the role bacteria plays in the health of mammals, the interdependence of plant and tree systems, and mutually supportive mechanisms of coral and algae. A beautiful example of an evolutionary relationship based on complementarity is that of bobtail squid, who developed its luminescence not from a genetic mutation, but from a collaboration with the glowing bacteria vibrio Fischeri. In this relationship, the conditions are as such where the fullest expression of one species set of traits can support the fullest expression of the other.

In the future, we’ll continue to learn more about biological relationships that aren’t born of competition, but in the present, there’s an opportunity, an urgent need, to understand this metaphor and put it into practice. Competition must no longer be understood as a sole evolutionary feature, or motivator for success. Favini continues: “One critical takeaway is that we must learn to recognize the impulse to naturalize a given human behavior as a political maneuver. Competition is not natural, or at least not more so than collaboration.”

A competitive mindset is in contrast to a complementarity one, where we understand difference as a potential for creativity; not judging it, or categorizing it within a hierarchy. We are fast-approaching a future in which the ability to healthily relate to one another will be the most important skill we can cultivate. If we are seeking biological examples to model our new systems on, we should aim for the ones where the most living beings are healthily thriving, like the complementarity found between mushrooms and trees, not those in which bloodshed of the less fortunate is the marker for success.

The Conscious and The Unconscious

Conscious and unconscious are two terms can be simply defined “what we know or are aware of” and “what we do not know and are unaware of”. Unconsciousness lies underneath what we know personally. Deeper still, the collective unconscious contains the unconscious patterning that has existed throughout human development, and continues to express itself in patterns of behavior, storytelling, and image making.

These two aspects of the individual and collective psyche are in constant dialogue with one another, and it is critical that any system hold them as complementary. We often devalue intuitive senses or emotions, diminishing this unmediated information coming from the unconscious, that may lead to great discoveries if we listen. The unconscious psyche, intuitive or visionary mind, supports us in the creative process. Many great discoveries happen first in the intuitive realm. This archetype of sudden realization through the unconscious carries down in innovation folklore with Archimedes in the tub exclaiming “Eureka!”, or the apple falling on Newton’s head.

Even the most technical, scientific, discoveries can have their roots in dream, visionary, or symbolic material, precisely because this material comes from the unconscious, and contains within it time-spanning resilience and structure. Watson, of DNA fame, saw the double-helix in a dream before he sketched it on paper. In a long work sprint, the chemist Mendeleyev who developed the period table of elements, pushed his body to the limit (exhausted states bring us closer to the unconscious), he then took a 20 minute nap and: “I saw in a dream a table where all the elements fell into place as required. Awakening, I immediately wrote it down on a piece of paper.” When we are open to the unconscious, we receive information that our conscious mind can process and make use of. For example, intuition and data are natural complements, but we often diminish the power of intuition because culturally we over-associate with data, placing more emphasis and validity on this conscious aspect. In a complementary relationship, data can validate intuition, creating a potent couplet. At all times, data must be guided back to the service of the system. When a system is over-leveraged in the conscious part of the psyche, it is no longer driven by creative potential, but by efficiency. Conversely, when a system is over-identified with the unconscious, it lacks discipline, organization, and realized outcomes.

Long-lasting innovations begin at the visionary, intuitive level, or initiate from a natural problem or circumstance. Innovations that are purely in service of maximizing a market opportunity do not have resilience or sustainability (across many metrics, not just a few). Paradoxically, in the undifferentiated “chaos” of the unconscious, there lies a deep resilience; it is the resilience found in nature that has sustained life throughout time. These are the structures that consciousness rests on, but does not circumvent or supersede. The principle of complementarity resides in the unconscious as a natural structure, and can emerge as a potential. When we consciously build systems with complementarity as a root principle, we are tapping to a structure of reality much more fundamental than the clever frameworks of our conscious psyche.

When applied to systems change, it is a lesson that new models must be derived from structures found in nature. Those working in biomimicry, or integrating aspects of indigenous and nature-based practices in novel expressions, intuitively understand this. For sustaining models, we cannot be over-identified with hyper-rationality, cleverness or impenetrable articulations (like algorithms). In concert with our conscious effort, the unconscious supports solutions that have their basis in the structures of nature. We must work in collaboration with the unknown as a source of innovation and emergent ideas.

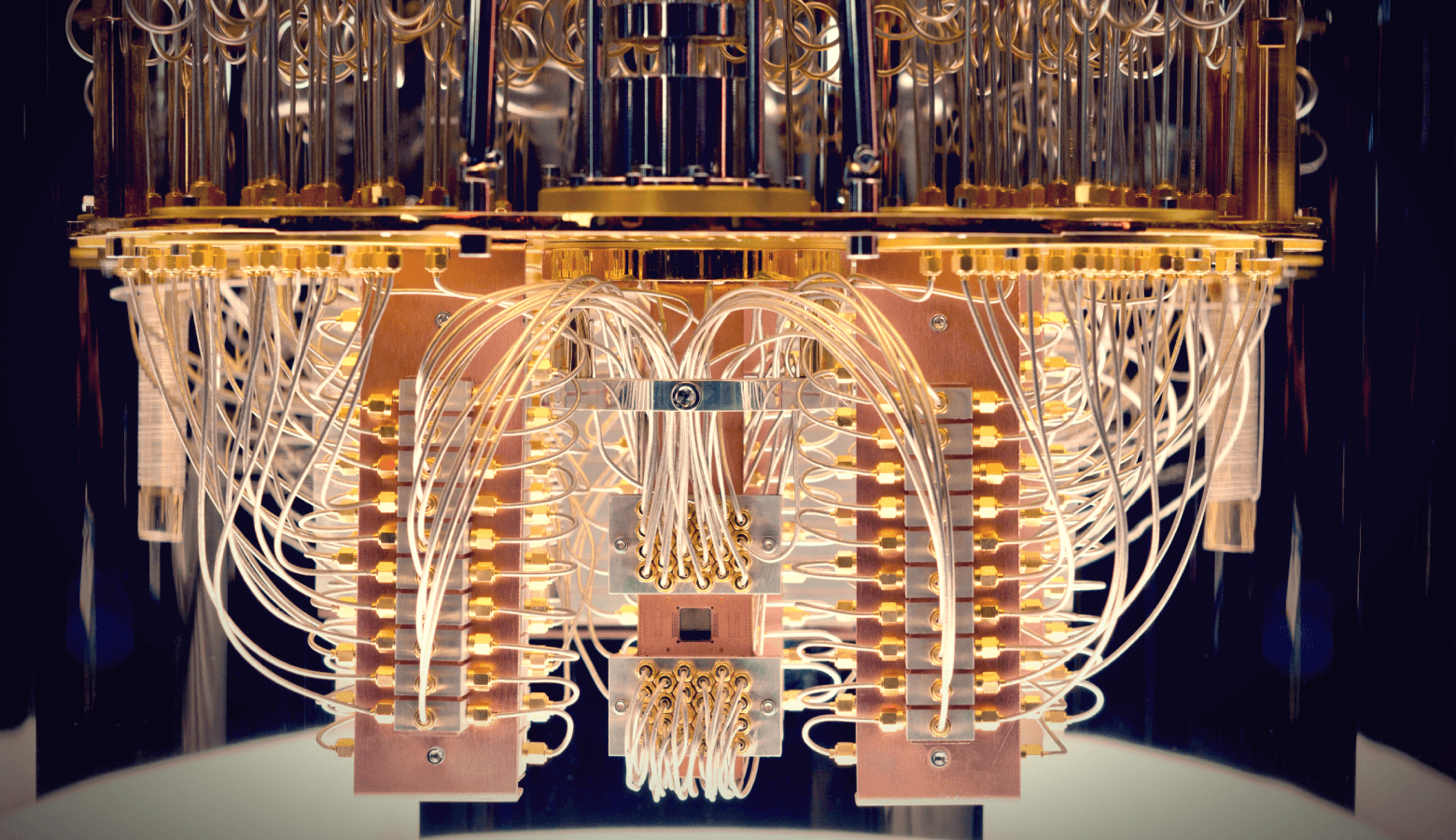

Quantum Computing

With the invitation to move away from exclusively binary models of thinking, the world of supercomputing is laying more metaphorical groundwork for an understanding of complementarity. Our existing computing systems are based on a binary model of 0 and 1, or a bit. This is essentially an “on” or “off” mechanism that in sequence, solves computing equations. This happens very fast, many times over, but at any moment, leaves room for only one possibility at a time. As we look to solve more complex problems, the binary model of computation is reaching its limits.

For exponentially more processing power, scientists are turning to a quantum model of computing, where binary bits are replaced with “qubits.” Rather than expressing the certainties of 0 or 1, qubits express “superpositions,” where many outcomes are possible at once. Quantum computers perform calculations based on the potential of an object's state before it is measured. Think of a coin that is constantly spinning, vs. a binary coin toss of a conclusive heads or tails measurement. Quantum computing allows for many possibilities at once and as a result, are able to solve problems in minutes that take our present-day binary computers lifetimes.

Quantum computing has also begun to unlock “entanglement,” the mysterious process of two objects in two different positions being demonstrably affected by one another by nature of their quantum entanglement, seeming to defy our Newtonian model of physics. This non-theoretical experimentation demonstrates us that if we setup complementary relationships, we will be amazed and humbled by the real-world results.

Scientists also have the humility to recognize the mystery of the process. Pan Jianwei, the head of China’s Quantum Satellite Project, describes quantum entanglement: “Although we don’t know what the physics are behind quantum entanglement, we do know it exists…we can still use such a phenomenon for a useful application.” Complementarity is a ground-truth of our reality that expresses itself in many arenas, and does not only live as a scientific principle. It points to a deeper aspect of how our world interacts, including the nature of our own consciousness.

It makes sense that the power of the quantum computing paradigm be ushered in with a corresponding complementary mindset so it can work for our cultural benefit and not against it. In the doomsday mythology of people vs. computers, a both/and perspective is critical. It is not one or other, a complete rejection of the machine or a surrender to it, but a “working with” that will mutually support our life. As new and exponentially more powerful technology evolves, we must work on the mindset that integrates it.

Mythology

“Myths are collective dreams and dreams are personal myths.” - Joseph Campbell

Myths are stories that we collectively write to make sense of the world around us, and myths eventually become part of the operating system that determines what we believe, how we act, and who we think we are.

The mythic realm is one of archetypes — images and instincts that emerge out of the unconscious and motivate our behaviors and symbol-making. Archetypes reflect deep patterning in nature and in our collective psychic storehouse, and these patterns of humanity make their way into the narratives of myths. When we examine myths consciously, instead of being unconsciously ruled by them, we can use them as a tool for more awareness about our human condition. The myths of the Greeks, instance, are taken to express many fundamental aspects of Western psychology. When we are unconsciously driven by myths, and the archetypes that underpin them, we are subject to their patterning and reinforcement. It’s no surprise that the last two thousand years of western mythmaking has been over-identified with a competitive, binary view of storytelling and we continue to be under its spell. Our collective mythmaking promotes the idea of lone heroism. Often a single, “good” hero who, through his (usually a male) own cunning or might, defeats some aspect of evil, and goodness prevails. We have seen the heroic conquering evil as a prevailing storyline. But what has been left out?

When we look around for myths that reflect the principle of complementarity, we find that they appear in false starts, in potentia, before storylines of domination and one-sidedness take over. In the Western mythmaking, complementary twin heroes usually succumb to this. The story of the root twins in the Bible for instance, Cain and Abel, ends with Cain killing Abel. Most telling is the story of Romulus and Remus, twin brothers who set out to found a new city. The brothers quarreled over which hill to build the city on, and instead of finding the complementary “third way” that could have occurred as a result of their mutual empathy, the quarrel ends in bloodshed. Romulus kills Remus, then goes on to found the city of Rome, confining the mythological tradition of killing off “the other” to maintain a sense of ideological rightness — instead of sacrificing our idea, we sacrifice one another. Rome was an empire built on mythic blood, and its brutal history and eventual downfall bore out accordingly. This has been the mythic and real-world patterning of modern history: going to war because of a refusal to surrender an idea.

In Navajo mythology we do find an incredible example of twin heroes in the story “When Two Came to Their Father”, which tells the story of “Monster Slayer,” and “Child Born of Water”, two brothers faced with the task of returning to their father Sun’s home. Throughout the story, these heroes must work together to complete their tasks, which includes crossing territories and defeating foes. Instead of domination or one-sidedness, we see wholeness and coherence, two parts working together in a common task, and it is no less dramatic. This myth touches the deeper, mostly unexpressed archetype of collaboration using our differences. Not only are the twin aspects of the whole system able to work together, their difference is the requirement for innovative solutions and ultimately, success.

Twin hero mythology speaks to the innate wholeness of systems, where nothing is left out. In this mythmaking, mutually reinforcing relationships are used to solve problems -- collaboration in service of creativity rather than destruction or one-sided rightness. We have to investigate for ourselves if, as a culture, we are addicted to the drama of opposites in tension and lone heroism. Good vs. evil is a story that has been reinforced over in our mythmaking, and it has shaped our culture accordingly. To rewire ourselves for sustainability, we can start by choosing to animate non-binary mythologies.

The symbolic language of Taoism expresses complementarity in one of its most elegant, symbolic forms. Complementarity is fact the root of taoism, to be in dynamic flow with twin energies as a creative principle. “Thirdness” exists in Taoism as a generational property that results from the inter-being of two polarities (points of view, perspectives, etc.) the result is something that is more than what is possible from two standing alone. One of the secrets of the Tao te Ching is that generation springs from two complementary aspects, dynamically working with each other in response to themselves and the environmental field — i.e. relating. We can see that complementary perspective is the consciousness that is most connected to the very nature of creation. It is the hidden link between all perceived opposites. As a Taoist proverb says: “The struggle of good and evil is the primal disease of the mind.”

The Sun and moon are one of nature’s most primordial examples of complementarity. A giving light and a receiving light, that correspond to the fertility on earth. These two complementary lights are pre-mythology, pre-gender, and pre-cultural associations, they exist in the archetypal unconscious as primordial, life-sustaining symbols. The sun and moon offer us a metaphorical system of complementarity that is free from the associations of religion, spirituality, or even psychology. When the moon’s light is full, it is in direct opposition to the sun. It should be obvious that we do not view nature in competition with itself, the sun and moon work in perfect unison to make life on earth possible. Interestingly, the ancient practice of alchemy used the sun and moon (“sol” and “luna”) as metaphors for joining the opposites in a creative union, or the “conunctio.”

In the last 100 years especially, we live a world of artificial light. It should be said that we are significantly over-leveraged in “solar” modes of thinking, which correspond to linearity, conscious processing (think Khaneman and Tvaresky’s “System 2). The lunar complement of non-linearity, empathy, and a relationship with the unconscious must be re-established for the health of global systems. In quantum terms, we culturally value the measurement of particle, over the wave. If we relate this to our mythmaking, we have sacrificed this aspect (remember Remus) in favor of a model that largely worships the sun and neglects its lunar twin. Most importantly, complementarity is a mindset that wholly depends on the lunar, empathic aspect as a mode of relating.

For more information on solar/lunar archetypes and their relationship to complementarity, view the work of Dr. Howard Teich

Get the quarterly newsletter

CONTACT US | OUR STORE | INSTAGRAM

hello@superiorbranding.co

©2022 Superior Branding Enterprises, Inc.